This post explores why experience is such an important part of the creative process and is part of my Creative Intelligence Archive Series. I hope you enjoy it.

I left school when I was 16, skipped sixth form college and A-Levels, choosing to spend the next seven years working my way through various design and art courses. Portsmouth College of Arts was, quite literally, my first port of call and I spent a year commuting on the slow, dreary train from Woolston to Portsmouth Harbour: stopping at every single station along the way.

I studied at Portsmouth College of Arts but was very rarely in the actual building because my course was in a grubby, windswept, community centre that had originally been a bricks and mortar school, the likes of which only Victorian Britain seemed capable of inflicting on people. It was called the John Pounds building or Centre. The old building has gone, and in its place stands the kind of community centre that only early millennial Britain seemed capable of inflicting on people.

I spent a year learning the basic crafts of art, design and being a student in that building. A thug once mugged me with a German Alsatian trying to get there. I drew his portrait for the police, the press published the story, and they caught him three days later: never mug an art student. I have many fond memories of the utterly miserable train journey too, but there is one story which I often recall when working with people who struggle with creating ideas or answering challenging business questions.

It’s the autumn of 1987, and we have been cautioned to behave ourselves and treat the situation and Sharon with the respect it, and she deserves: the situation is a life drawing class, and Sharon is an adult woman without any clothes on. I’d never been in a room with a naked woman before and painting Sharon was most certainly a change to sketching my dad as he slumbered, fully clothed, in his armchair. We positioned ourselves around the room, set up our easels, unpacked our brushes and began to paint.

A very tall man named John and the ever so slightly creepy Mike.

The lecturer running the course is a very tall man named John. I can’t remember his surname, but I do remember that he lived in Winchester, and would later introduce me to the works of Australian artist Arthur Boyd. John was a patient man and observed our progress with that mix of amusement and frustration that seems to come with the territory of teaching. It was during the third session that John stopped the class and asked us to come and look at Mike’s painting of Sharon. Mike was a slightly creepy mature student who had chosen to sit directly in front of Sharon. He and Sharon were about the same age and had been casually chatting to each other, both seemingly oblivious to the fact that one of them was naked. Mike’s painting was brilliant, and everyone in the room could see it.

The naked and the red.

John asked us to go back and compare our work with that of Mike and try and figure out the difference. Mike’s painting was vibrant, full of colour: the picture wasn’t only a likeness of Sharon, but it felt alive and exciting. My canvas looked lifeless: a female form, pink and red around the edges. It was a dead, adolescent depiction of what a sixteen year old boy thought a portrait of a naked woman should be.

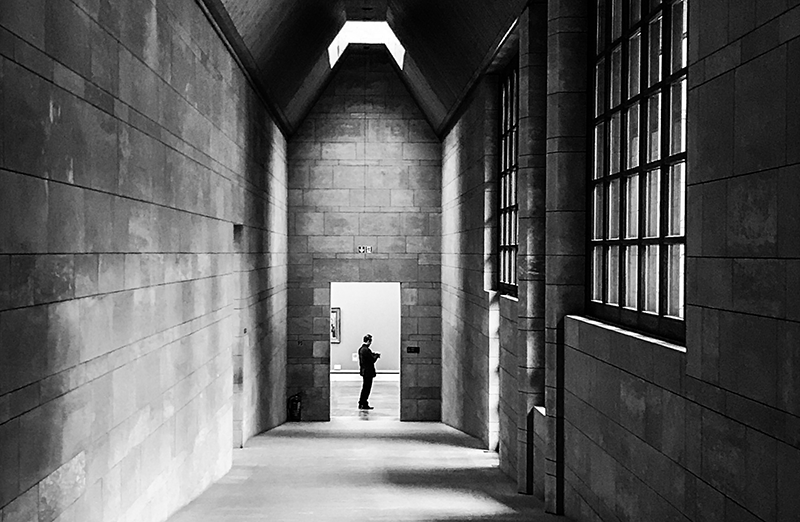

“You have limited palettes,” John informed us and sent us off home. That weekend I went to Southampton City Art Gallery and tried to work out how to paint people. I bought additional colours, thus extending my palette. I felt confident that I might be able to save my blobby version of Sharon. The sessions continued for weeks with most of us struggling with John’s palette advice and Mike chatting with Sharon about shopping, Eastenders and the weather, while effortlessly knocking out one remarkable painting after the other.

It was frustrating, and during my end of term one-to-one with John, I told him so. I felt disappointed with myself and simply couldn’t understand why, even though I had the same colours and paints and Mike, I wasn’t nailing it like Mike. “He’s spent much more time in the library looking at how other artists paint than any of you, and he has practised. Marcus, Mike is a grown man: he has slept with women, lusted after women and he has loved women. He knows the touch of their skin, the smell of their hair: he’s been up close to them, and he has heard their hearts beat. His paintings of Sharon are better than yours because he understands the concept and context of Sharon as a person. He talks to her. He might even love her for all I know. He has a broader palette of experience, Marcus.”

I often think of John, Mike and Sharon when I’m working with younger teams or groups of people so completely focused on the tools and processes of getting things done. Answers to commercial questions are more often found by folding the contents of the treasure chest of personal experience into expert knowledge and not by extending the tool-set you think you need. I return to the story of the life drawing class when I’m struggling myself, just to remind myself that the elusive answer to a formidable question may lie in understanding that something is missing, hidden somewhere in a place that I have yet to experience. The trick is to discover what’s missing, find it and then immerse yourself in it.

The Creative Intelligence Archive.

The Archive contains all the things you’ve experienced as well as all of the things you’ve studied and learned along the way. It’s the place you go to when you’ve been asked a question, given a brief or asked to design a new service. It is the palette with which you paint answers, which is why it’s important to keep it topped up with fantastic things. It’s notebooks, sketchbooks, Evernote archives, Pocket bookmarks, Instagram moments, books, indie magazines, research papers, holidays, weekends away, walks, people watching and conversations with complete strangers. All it takes is a little investment in time and effort to actively seek out and learn something new, put yourself in situations where you can stumble upon the unexpected and the unusual.